A Simple Guide to ES6 Promises

The woods are lovely, dark and deep. But I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep. — Robert Frost

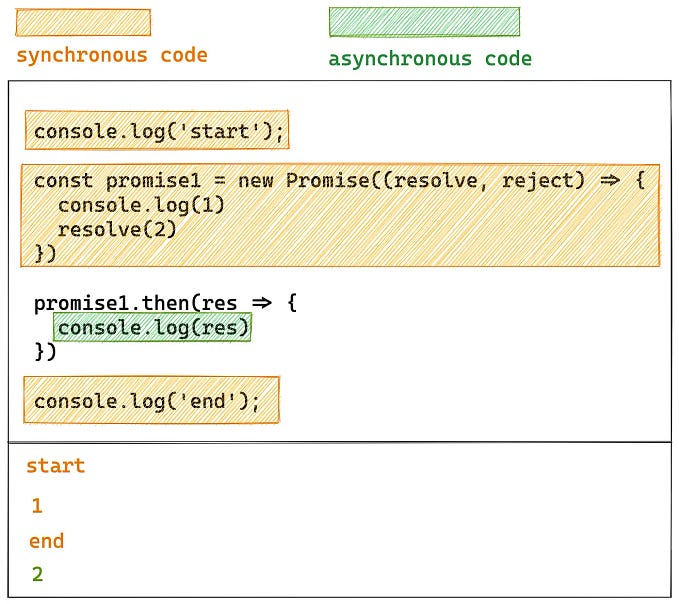

Promises are one of the most exciting additions to JavaScript ES6. For supporting asynchronous programming, JavaScript uses callbacks, among other things. However, callbacks suffer from problems like Callback Hell/Pyramid of Doom. Promises are a pattern that greatly simplifies asynchronous programming by making the code look synchronous and avoid problems associated with callbacks.

In this article we are going to see what are promises, and how can we leverage them to our advantage.

What is a Promise?

The ECMA Committee defines a promise as —

A Promise is an object that is used as a placeholder for the eventual results of a deferred (and possibly asynchronous) computation.

Simply, a promise is a container for a future value. If you think for a moment, this is exactly how you use the word promise in your normal day-to-day conversation. For example, you book a flight ticket to go to India for travelling to the beautiful hill station Darjeeling. After booking, you get a ticket. That ticket is a promise by the airline that you will get a seat on the day of your departure. In essence, the ticket is a placeholder for a future value, namely, the seat.

Here’s another example — You promised your friend that you would return their book The Art of Computer Programming after reading. Here, your words act as the placeholder. The value is the said book.

You can think of other promise-like examples relating to various real-life situations like waiting at a doctor’s office, ordering food at a restaurant, issuing a book in a library, among others. All involve some form of a promise. However, examples only take us so far. Talk is cheap, so let’s see the code.

Making Promises

We create a promise when a certain task’s completion time is uncertain or too long. For example — A network request may take anywhere between 10ms to 200ms (or more) depending on the connection’s speed. We don’t want to wait while the data is being fetched. 200ms may seem less to you but it’s a (very) long time for a computer. Promises are all about making this type of asynchrony easy and effortless. Let’s get to the basics.

A new promise is created by the using the Promise constructor. Like this —

Observe that the constructor accepts a function with two parameters. This function is called an executor function and it describes the computation to be done. The parameters conventionally named resolve and reject, mark successful and unsuccessful eventual completion of the executor function, respectively.

The resolve and reject are functions themselves and are used to send back values to the promise object. When the computation is successful or the future value is ready, we send the value back using the resolve function. We say that the promise has been resolved.

If the computation fails or encounters an error, we signal that by passing the error object in the reject function. We say that the promise has been rejected. reject accepts any value. However, it is recommended to pass an Error object since it helps in debugging by viewing the stacktrace.

In the above example, Math.random() is used to generate a random number. In 90% of the cases, the promise will be resolved (assuming equal probability distribution). It will be rejected in the rest of the cases.

Using Promises

In the above example, we created a promise and stored it in myPromise. How can we access the the value passed by the resolve or reject function?All Promise instances have a .then() method on them. Let’s see —

.then() accepts two callbacks. The first callback is invoked when the promise is resolved. The second callback is executed when the promise is rejected.

Two functions are defined on line 10 and 11, onResolved and onRejected. They are passed as callbacks to the .then() on line 13. You can also use the more idiomatic style of writing a .then as done in line 16 to 20. It offers the same functionality as the above .then.

A few important things to note in the previous example.

We created a promise myPromise. We attached a .then handler two times: on line 13, and 16. Though, they are same in functionality, they are treated as different handlers. However —

- A promise can only succeed(resolved) or fail(reject) once. It cannot succeed or fail twice, neither can it switch from success to failure or vice versa.

- If a promise has succeeded or failed and you later add a success/failure callback (i.e a

.then), the correct callback will be called, even though the event took place earlier.

That means once the promise reaches a final state, the state won’t change (that is, the computation will not be done again ) even if you attach .thenhandler multiple times.

To verify this, you can see a console.log statement on line 3. When you run the above code with both .then handler, the logged statement will be printed only once. It shows that the promise caches the result, and will give the same result next time.

The other important thing to note is that a promise is evaluated eagerly. Itstarts its execution as soon as you declare and bind it to a variables. There is no .start or .begin method. Like it began in the previous example.

To ensure that promises are not fired immediately but evaluates lazily, we wrap them in functions. We’ll see an example of this later.

Catching Promises

Till now we conveniently saw only the resolve cases. What happens when an error occurs in the executor function. When an error occurs, the second callback of .then(), that is, onRejected is executed. Let’s see an example —

It’s the same as first example, but now it rejects with 90 percent probability and throws an error in 10% of the cases.

On line 10 and 11 we have defined onResolved and onRejected callbacks , respectively. Note that onRejected will be executed even if an error was thrown. It’s not necessary to reject a promise by passing an error in the reject function. That is, a promise is reject in both cases.

Since error handling is a necessity for robust programs, a shortcut is given for such a case. Instead of writing .then(null, () => {...}) when we want to handle an error, we can use .catch(onRejected) which accepts one callback: onRejected. Here’s how the above code will look with a catch handler —

myProimse.catch(

(error) => console.log(error.message)

);Remember that .catch is just a syntactical sugar for .then(undefined, onRejected).

Chaining Promises

.then() and .catch() methods always return a promise. So you can chain multiple .then calls together. Let’s understand it by an example.

First, we create a delay function that returns a promise. The returned promise will resolve after the given number of seconds. Here’s its implementation —

const delay = (ms) => new Promise(

(resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, ms)

);In this example, we are using a function to wrap our promise so that it does not execute immediately. The delay function accepts the time in milliseconds as a parameter. The executor function has access to the ms parameter due to closure. It also contains a setTimeout that calls the resolve function after ms milliseconds pass, effectively resolving the promise. Here’s an example usage —

delay(5000).then(() => console.log('Resolved after 5 seconds'));The statements in the .then callback will run only after delay(5000)resolves. When you run the above code, you’ll see Resolved after 5 secondsprinted five seconds later.

Here’s how we can chain multiple .then() calls —

We begin at line 5. The steps undertaken are —

- The

delay(2000)function returns a promise that gets resolved after two seconds. - The first

.then()executes. It logs a sentenceResolved after 2 seconds. Then, it return another promise by callingdelay(1500). If a.then()returns a promise, the resolution (technically called settlement) of the that promise is forwarded to next.thencall. - This continues as long as the chain is.

Also note line 15. We are throwing an error in the .then. That means the current promise is rejected, and is caught in the next .catch handler.Hence, Caught an error gets printed. However, a .catch itself is alwaysresolved as a promise, and not rejected (unless you intentionally throw an error). That’s why the .then following .catch is executed.

It is recommended to use .catch and not .then with both onResolved and onRejected parameters. Here’s a case explaining why —

Line 1 creates a promise that always resolves. When you have a .then with two callbacks, onResolved and onRejected, you can only handle errors and rejections of the executor function. Suppose that the handler in .then also throws an error. It won’t lead to the execution of onRejected callback as shown on lines 6–9.

But if you have a .catch a level below the .then, then the .catch catches errors of executor function and the errors of .then handler too. It makes sense because .then always returns a promise. It is shown on line 12–16.

You can execute all the code samples, and learn more by doing. A good way to learn is by implementing callback-based functions into promises. If you work with Node, a lot of functions in fs and other modules are callback-based. There do exist utilities that can automatically convert a callback-based function to promises such as Node’s util.promisify and pify. But, if you are learning, consider applying the WET (Write Everything Twice) principle and re-implement or read the code of as much libraries/functions as possible. Use DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle every other time especially in production.

There are many other things that I have not been able to cover such as Promise.all ,Promise.race and other static methods. Handling errors in promises, and some common anti-patterns and gotchas to be aware while making a promise. You can reference the below articles for a more understanding on these topics.

Do respond to this article if you want me to cover those topics in another article! :)

References

- ECMA Promise Specification, Mozilla Docs, Google’s Developer’s Guide on Promises written by Jake Archibald, Exploring JS’s Chapter on Promises, and Introduction to Promises.

I hope you enjoyed this guest post! This article was written by Arfat Salmon exclusively for CodeBurst.io

Closing Notes:

Thanks for reading! If you’re ready to finally learn Web Development, check out: The 2018 Web Developer Roadmap.

If you’re working towards becoming a better JavaScript Developer, check out: Ace Your Javascript Interview — Learn Algorithms + Data Structures.

Please consider entering your email here if you’d like to be added to my once-weekly email list, or follow me on Twitter.