Diving Deep Into The Golang Channels.

An “ins and out” of the internal implementation of the Golang channels and its related operations.

Concurrency in Golang is much more than just syntax.

It a design pattern.

A pattern that is a repeatable solution to a commonly occurring problem while working with concurrency, because even

Concurrency Needs to be Synchronized.

And Go relies on a concurrency model called CSP ( Communicating Sequential Processes), to achieve this pattern of synchronization through Channel. Go core philosophy for concurrency is

Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.

But Go also trusts you to do the right thing. So Rest of the post will try to open this envelope of Go philosophy and how channels — using a queue to achieve the same.

What it takes to be a Channel.

func goRoutineA(a <-chan int) {

val := <-a

fmt.Println("goRoutineA received the data", val)

}func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go goRoutineA(ch)

time.Sleep(time.Second * 1)

}

So it’s Responsibility of channel in Go to make the Goroutine runnable again that is blocked on the channel while receiving the data or sending the data.

If you are unfamiliar with Go Scheduler please read this nice introduction about it. https://morsmachine.dk/go-scheduler

Channel Structure

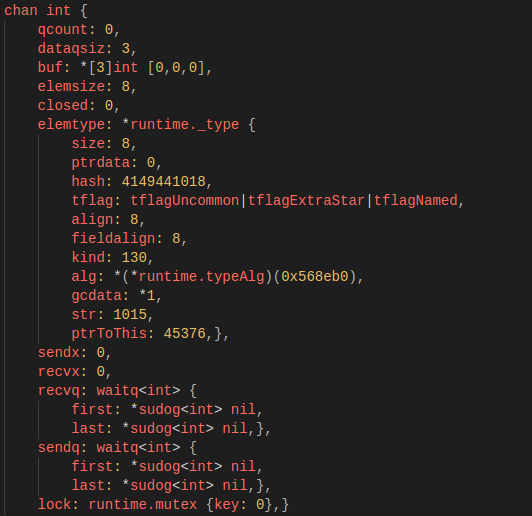

In Go, the “channel structure” is the basis of message passing between Goroutine. So What does this channel structure looks like after we create it?

ch := make(chan int, 3)

Looks good, good. But what does this really mean? and from where channel gets its structure. Let’s look at a few important structs before going any further.

hchan struct

When we write make(chan int, 2)channel is created from the hchan struct, which has the following fields.

Lets put descriptions to a few fields that we encountered in the channel structure.

dataqsize Is the size of the buffer mentioned above, that is make(chan T, N), the N.

elemsize Is the size of a channel corresponding to a single element.

buf is the circular queue where our data is actually stored. (used only for buffered channel)

closed Indicates whether the current channel is in the closed state. After a channel is created, this field is set to 0, that is, the channel is open; by calling close to set it to 1, the channel is closed.

sendx and recvx is state field of a ring buffer, which indicates the current index of buffer — backing array from where it can send data and receive data.

recvq and sendq waiting queues, which are used to store the blocked goroutines while trying to read data on the channel or while trying to send data from the channel.

lock To lock the channel for each read and write operation as sending and receiving must be mutually exclusive operations.

So what is this sudog?

sudog struct

sudog represent the goroutine.

Let’s try to wrap our head around the channel structure again step by step. It’s important to have a clear picture of these as this is what gives channel the power in Go.

What will be the structure of the channel before line No 22?

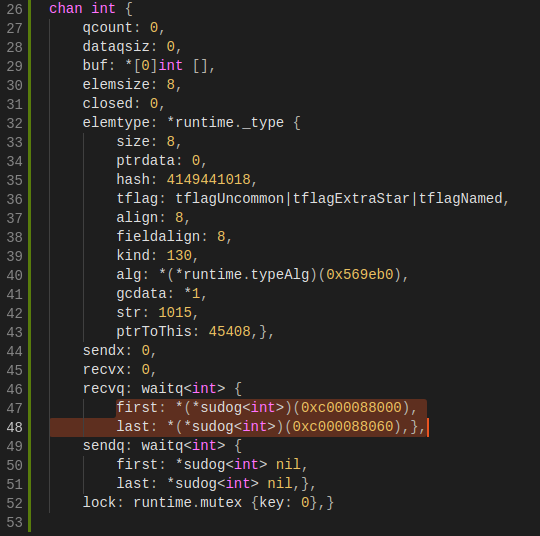

Pay attention to highlighted line no 47 and 48 above. Remember recvq description from above

recvq are used to store the blocked goroutines which are trying to read data from the channel.

In Our Example Code before line 22 there are two goroutines (goroutineA and goroutineB ) trying to read data from the channel ch

Since before line 22 on a channel, there is no data we have put on the channel so both the goroutines blocked for receive operation have been wrapped inside the sudog struct and is present on the recvq of the channel.

sudog represent the goroutine.

recvq and sendq are basically linked list, which looks basically as below

These structures are really Important,

Let’s see what happens when we try to put the data on the channel ch

Send Opertaion Steps c <- x

Underlying types of send Operations on Channel

- sending on nil channel

If we are sending on the nil channel the current goroutine will suspend its operation.

2. sending on the closed channel.

If we try to send data on the closed channel our goroutine panic.

3. A goroutine is blocked on the channel: the data is sent directly to the goroutine.

This is where recvq structure plays such an important role. If there is any goroutine in the recvq it’s a waiting receiver, and current write operation to channel can directly pass the value to that receiver. Implementation of the send function.

Pay attention to the line number 396 goready(gp, skip+1) the Goroutine which was blocked while waiting for the data has been made runnable again by calling goready, and the go scheduler will run the goroutine again.

4. Buffered Channel if there is currently space available for hchan.buf: put the data in the buffer.

chanbuf(c, i) accesses the corresponding memory area.

Determine if hchan.buf has free space by comparing qcount and dataqsiz. **Enqueue the element by copying the area pointed to by the ep pointer to the ring buffer to send**, and adjust sendx and qcount.

5. The hchan.buf is full

Create a goroutine object on the current stack

acquireSudog to put the current goroutine in the park state and then add that goroutine in the sendq of the channel.

Send operation Summary

- lock the entire channel structure.

- determines writes. Try

recvqto take a waiting goroutine from the wait queue, then hand the element to be written directly to the goroutine. - If recvq is Empty, Determine whether the buffer is available. If available, **copy** (

typedmemmovecopies a value of type t to dst from src.`) the data from current goroutine to the buffer.

_typedmemmove_ internally uses memmove — memmove() is used to copy a block of memory from a location to another. - If the buffer is full then the element to be written is saved in the structure of the currently executing goroutine and the current goroutine is enqueued at sendq and suspended, from runtime.

Point number 4 is really Interesting.

If the buffer is full then the element to be written is saved in the structure of the currently executing goroutine.

Read it again, because this is why the unbuffered channel is actually called “unbuffered” even though the “hchan” struct has the “buf” element associated with it. Because for an unbuffered channel if there is no receiver and if you try to send data, the data will be saved in the elem of the sudog structure. (Holds true for the buffered channel too).

Let me give you an example to clarify the point number 4 in more details. Suppose we have the below code.

What will be the runtime structure of the chan c2 at line number10 ?

You can see even though we have put int value 2 on the channel the buf does not have the value, but it will be in the sudog structure of the goroutine. As goroutineA tried to send value over to the channel c2 and there were no receiver ready, so the goroutineA will be added to sendq list of the channel c2 and will be parked as it blocks. We can look into the runtime structure of the blocking sendq to verify.

Now that we have overview of send operation on channel what happens once we send an value to our example code above at line 22.

ch <- 3As recvq of the channel has goroutine in wait state, it will dequeue the first sudog and put the data in that goroutine.

Remember all transfer of value on the go channels happens with the copy of value.

What will be the output of the above program ? Just Remember Channel Operates on the copy of value.

So in our case channel will copy the value at g into its buffer.

Don't communicate by sharing memory; share memory by communicating.

Output

&{Ankur 25}

modifyUser Received Value &{Ankur Anand 100}

printUser goRoutine called &{Ankur 25}

&{Anand 100}

Receive Opertaion Steps <- ch

Its pretty much the same as the send operations

Select

Multiplexing on multiple channel.

- Operations are mutually exclusive, so need to acquire the locks on all involved channels in select case, which is done by sorting the cases by Hchan address to get the locking order, so that it does not lock mutexes of all involved channels at once.

sellock(scases, lockorder)Each scase in the scases array is a struct which contains the kind of operation in the current case and the channel it’s operating on.

kind Is the type of operation in the current case, can be CaseRecv, CaseSend and CaseDefault.

2. Calculate the poll order to shuffle all involved channels to provide the pseudo-random guarantee and traverse all the cases in turn according to the poll order one-by-one to see if any of them is ready for communication. This poll order what makes select operations to not necessarily follow the order declared in the program.

3. The select statement can return as long as there is a channel operation that doesn’t block, without even need to touch all channels if the selected one is ready.

3. If no channel currently responds and there is no default statement, current g must currently hang on the corresponding wait queue for all channels according to their case.

sg.isSelect is what indicates that goroutine is participating in the select statement.

4. Receive, Send and Close operation during Select Operation is similar to the general operation of Receive, Send and Close on channels.

Conclusion

Channels is a very powerful and interesting mechanism in Go. But in order to use them effectively you have to understand how they work. Hope this article explain the very fundamental working principle involved with the channels in Go.

Interested to learn more about Go? Come Join Us at Go Study Group

The study group is a great way to not only lurk ‘n learn but meet other people in the community. Everyone welcome!

Learned something? Clap your 👏 to help others find this article.

✉️ Subscribe to CodeBurst’s once-weekly Email Blast, 🐦 Follow CodeBurst on Twitter, view 🗺️ The 2018 Web Developer Roadmap, and 🕸️ Learn Full Stack Web Development.