Functional Programming in Javascript — Part II

In the first installment of this series, we discussed the foundations of functional programming as well as some of the essential patterns of functional programming such as compose, pipe, and curry. This article is about applying these patterns to the real world.

While there are plenty of articles that discuss functional programming (FP) functions through the use of primitive and contrived number array examples, I find that these often leave me confused. I understand the functions but am unsure as to how to start using them in my projects. Furthermore, I am often left wondering how to shift my mindset to writing more declarative code than imperative code. Because of this, I decided to write my own articles listing what I have learned about FP through my own experience.

Agenda

A great way to begin growing your skills is through practice. Start by doing some exercises, such as forking any open source JS/TS project from GitHub or any of your past projects and revamp sections in FP one by one. Using this method you’ll start discovering the patterns as you go along. This article will also take you through an exercise looking at how to make a simple real-world todo app using a lot of FP.

Codesandbox Link

Partial application & Currying

Suppose you have this simple structure and helper for managing a todo in your app which has its text and current status as either active or completed.

Imagine that you have to make an active todo every time you make a new todo. It would be nice to have a helper function that could wrap our original makeTodo fn and partially apply the first argument as TodoStatus.Active . Then you just need to pass one argument as the todo text.

We can do this very easily using Ramda partial utility as.

This does exactly what we need. We can pass any number of arguments as the second parameter of partial function and they’ll get applied to the first argument function, returning another function which accepts the remaining arguments for that function.

For example, in this case, we passed one argument to the makeTodo function; the result of R.partial returns another function which will accept one remaining argument to execute its function body. If you examine this carefully you’ll see that R.partial is acting as a higher-order function such that it takes a function, modifies that function a little bit, and returns another new function. This concept of creating functions out of functions is at the very heart of FP and is something that we’ll find ourselves doing a lot throughout our FP project.

Here is a simple pure function that updates the status of a given todo:

We’ll see its application later in our project (this is why it was so useful to curry it).

Statements

A lot of imperative code is based on equality checks, if else, or ternary operator conditionals. Now, we’ll see how we can write them more declaratively. Below are some code excerpts from our presentational TodoItem.tsx component:

Now consider the following:

Equals

We just extracted the logic in another function and made our JSX more readable but we can compose the getCheckedValueFromStatus very easily from Ramda equals functions as:

What this does is creates a function that takes the LHS of the expression as its argument, equates it with TodoStatus.Completed , and returns a boolean. These are just small wins, but wait till you see the big picture!

IfElse

Consider this example, where we need to strike the checked todos as:

Not only are we making use of our last resulting boolean variable isChecked (which wouldn’t be possible if we had used it as a ternary expression in JSX as we did earlier), but we’re also making our component JSX more readable. By looking at each statement, we can do what it’s doing rather than reading the whole code as a story because we’re employing pure functions to use without worrying about any side-effects. Also, the ifElse logic of the getLineDecoration function isn’t tied to any boolean variable in particular, so we can use it to deduce line decoration value from, say, any other boolean variable other than isChecked. This is the level of code sharing that’s possible with FP.

We’re writing logics in the form of individual tiny functions and then composing them to create other functions, just like we make web components.

Note: It’s ok if you don’t want to use such overkill Ramda ifElse instead of a ternary operator or switch case. As long as you’re writing individual pure functions it doesn’t matter. But if you’re used to writing brief code using Ramda, these can be very helpful utilities during function composition operations.

Path

Another simple util to be used is R.path which works as lodash.get as:

This will simply extract the nested event.target.checked property.

An observation that you may have made already is that we’re declaring functions first with their logic, and then passing them the argument to apply that logic on to later on.

Compose & Pipe

Until now, you might have been finding it a little silly to do such a hardcore level of conversion to functions; you might be feeling skeptical about whether this is really worth doing. Well, check out the example below that explains why we’ve gone into such detail here.

Imagine that we now have to make an event handler for onChange of the checkbox. You may be tempted to do something like this:

Consider breaking it into steps as per the following:

This is still imperative and not a pure function, so let’s convert these series of imperative steps into an FP construct and build our handleOnChange function without writing any curly braces through function piping or composition.

Compose

We end up with a resulting pure function which — when simply given a checkbox change event — performs all of the operations step by step in the right to left argument fashion.

If you’re using Typescript you may have to go a little further here, as shown below:

These are “FUNCTIONS” in the actual sense. The earlier implementation of the ironic function handleChange(e) {...} is not a function but rather a “PROCEDURE”.

Note: If you find R.compose a little confusing then you can use R.pipe as it works in the left to right fashion as our brain is also wired that way (it’s just a matter of personal choice).

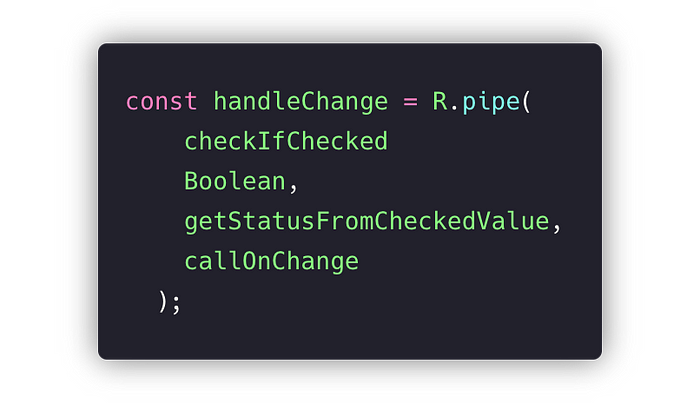

Pipe

Just by looking at it, it’s clear what handleChange but here’s a simple overview:

- It checks if the change event resulted in a check or uncheck of the checkbox.

- It converts it to a boolean

- It gets the equivalent “todo” status value from the checked value

- It calls the onChange function to emit output to the parent React component.

The good news here is that, if any of these four functions logic is needed elsewhere in the component, they can be re-used.

Hence, piping and composition can become very easy if you write everything in terms of functions.

Lens

A very sophisticated FP pattern, viz lenses is a very neat and useful way of handling what we call getters and setters in general programming lingo. Suppose we want to target one of the elements in an array at a given index, we might want to retrieve its current value and maybe update it. This may sound familiar in that we could update a single todo status inside our todos array.

What this is doing is focusing on a targeted part of our data structure which could be an object or an array (as in our case) and we’re focusing a single todo at todoIndex. Using this changedTodoLens, we can now perform getter and setter operations.

View

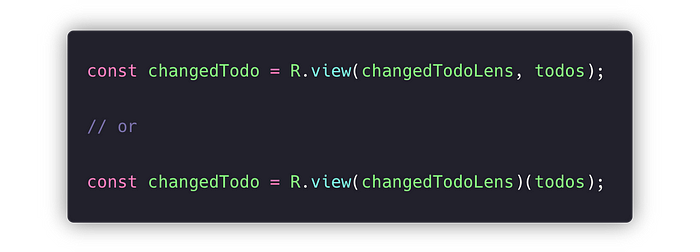

Here’s how the getter for the given lens works:

We’re viewing what we’re focusing on through the changedTodoLens using R.view.

Note: All built-in Ramda functions are curried, so either of the above invocations are valid.

Set

As you might have guessed, the signature looks like this:

Over

When you don’t have the cooked up value to replace at the given lens focused position, R.over can be used to pass a function to create the new value on the fly and update the lens position. Which is what we need in our case, as shown below:

If you recall from the first section, we created a changeTodoStatus helper and curried it, in order to fit here perfectly:

Simplifying our changeTodo function above, it would look like this:

This clearly demonstrates the benefits of Currying. Currying helps functions fit together by making their shape flexible

By converting a binary function (a function that takes to arguments) into a unary function (through currying and partially applying one argument), we made it possible to pass it as a second parameter to the R.over function which gives todo as an argument to that function. As you become comfortable with FP, you’ll find that you’re doing this quite frequently. For example, consider a function from a third party lib that takes arguments as:

In this instance, you find yourself making get calls all the time as per the following:

You can’t possibly perform this, since the constructURL function in the pipeline outputs a single argument as a URL to be passed to the next callback function, but sadly it’s not unary and even the order of the args is messed up.

Flip

The only option left is to reshape the makeAjaxCall function by flipping its arguments as follows:

By flipping the arguments, not only can we now can pass arguments in the reverse/flipped order, but we can also enjoy a curried variant, partially apply parameters to that function, and use it to easily build our fetchData function!

Conditionals

One of the requirements of the todo app input is to let the user type and update the value while monitoring a keystroke of enter, and performing an add todo operation.

When

R.when accepts a predicate function as its first argument which returns a boolean. Only when true does it proceed with the execution of the succeeding function passed into it (which is getting the input element current value and adding a todo based on it).

Unless

Very similar to when, the unless keyword is like the negation or opposite of when. For example, we want to only add the todo when it doesn’t exist already in the list (so as to avoid duplicate entries such as the following).

Every time you hit the enter key, it’ll keep on adding the “Do Yoga” todo into the list. To avoid this, we can use the unless higher-order function as follows:

Here, only when the checkIfTodoExists(todos)(text) returns false will it execute handleAddTodo(text).

Summary

There are plenty of Ramda functions worth learning and putting to use, however, it’s impractical to discuss all of them here. It’s important to note that the Ramda docs are very lucid with examples so it’s only through practical usage in your code that you will be able to gain a good understanding of these functions.

We have covered a few of the popular functions, including conditionals, expressions, lenses, composition and piping, and currying. We also saw how we could manipulate our thinking while writing a mundane todo world react app. Through this, it’s clear that all we need to do is put on our FP glasses to observe and embark on the journey of writing imperative procedures into pure functions and compose them together using the techniques we discussed above.

Outro

On a closing note, please do not jump to conclusions like saying that functional programming is bad or good. It’ll take some time to get adjusted to this method but once you’ve locked it in you won’t look back. Be patient, writing in FP is not something you learn overnight. It’s only through practice coding that you’ll start noticing these FP patterns every now and then. Personally, I am no expert here but I continue to develop these skills so as to see improvements.

It’ll seem very alluring to give up on writing declarative code in the beginning because of our comfort level with writing imperative code. It’s only in the long run that you’ll realize how helpful of a skill it is to be able to use code sharing and compose new functions from other functions in a jiffy.

Recommended Learning resources

I highly recommend this link:

It’ll help in learning Ramda through examples.

And, of course, the Ramda docs:

Thank you! Happy Coding 🤓

Please subscribe to my channel for FrontEnd tutorials