JavaScript error messages && debugging

Most of your time as a developer is spent reading code followed by debugging that same code, most likely to be able to read it or solve an “unexpected feature” (which, joking aside, is more correctly known as a “bug”).

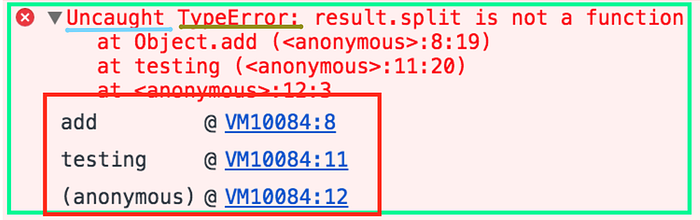

This is a sample of an error, the green is the overall error message, the light blue is to note if the error was properly handled, the brownish (dark yellow) is the type of error and the red is the call stack

The code that was run was the following (this is code for example purposes):

(function testing(){

var obj = {

add

} function add(a, b) {

var result = a + b

return result.split('')

} var stringResult = obj.add("1", "2")

var result = obj.add(1, 2)

})()

I will come back to this code in the call stack section, let us first see what the types of error can be.

Types of error messages

The first thing that indicates you that something is wrong with your code is the (in)famous error message that the one we saw just moments ago, it usually appears on your console (being developer tools of the browser, terminal or whatever else you are using).

For those already used to programming, reading an error message is like second nature, for everybody else, is something you learn either you like it or not so might as well talk a bit about each of them.

Reference errors

This is as simple as when you try to use a variable that is not yet declared you get this type os errors.

console.log(foo) // Uncaught ReferenceError: foo is not definedThis is also a common thing when using const and let, they are hoisted like var and function but there is a time between the hoisting and being declared so when you try to access them a reference error occurs, the fact that this happens to let and const is called Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ).

foo = 'Hello' // Uncaught ReferenceError: foo is not defined

let fooWhatever you are using (var, let or const) the fix is as simple has declaring the variable before any declaration is made.

let foo;

foo = 'Hello'Syntax errors

I know it’s in the name of the errors, but like it says itself, this occurs when you have something that cannot be parsed in terms of syntax, like when you try to parse an invalid object using JSON.parse.

JSON.parse( {'foo': 'bar'} ) // Uncaught SyntaxError: Unexpected token o in JSON at position 1This can be solved by just fixing the syntax, in this case the object should be a JSON.

JSON.parse('{"foo":"bar"}')Some syntax errors like sending a trailing comma when calling a function are handled without error by most recent browsers, but older ones you have to be careful.

Range errors

Try to manipulate an object with some kind of length and give it an invalid length and this kind of errors will show up.

var foo= []

foo.length = foo.length -1 // Uncaught RangeError: Invalid array lengthAn array for instance cannot have a negative length, why would you mess with the array length? Some people use it to set an array to empty, something of the likes of:

var foo = [0, 0]

foo.length = foo.length - 2 // (or foo.length - foo.length)

foo // would log [] instead of [0, 0]I prefer not to mutate my variables whenever possible (making them constants and not variables) but this is a method that is available and now you know it.

Type errors

Like the name indicates, this types of errors show up when the types (number, string and so on) you are trying to use or access are incompatible, like accessing a property in an undefined type of variable.

var foo = {}

foo.bar // undefined

foo.bar.baz // Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'baz' of undefinedThis is probably the most frequent error in JS, trying to access a property/method thinking that bar is of the type object when in reality, since it hasn’t been declared yet, it’s undefined which doesn’t have any baz available.

The fix is simple, just make sure that bar exists before trying to access it, either by creating bar or by checking for undefined.

var foo = { bar: {} }

foo.bar.baz // undefined but you avoid the erroror

var foo = {}

if (typeof foo.bar !== 'undefined') {

foo.bar.baz // this will never be executed while bar does not exist

}- There are also warnings, for instance telling you about a deprecated method, which can be found more frequently in firefox developer tools.

For a full list of errors you can check out MDN

Debugging

To debug your JS code, the easiest and maybe the most common way its to simply console.log() the variables you want to check or, by using chrome developer tools, open your page with your JS code (press cmd+o in macOS or Ctrl+o in Windows) and choose your file to debug, click the line you wanna debug and refresh your page again (F5).

If the line you selected was run you will be able to see what has happened before that point and you can try and evaluate the next lines to check if everything is outputting what you are expecting.

The breakpoint can also be achieved by putting a debugger statement in your code in the line you want to break.

You can also add conditional breakpoints by right-clicking a previous set breakpoint, which will make your program stop at that point only if a condition is met, this is awesome for when you want to debug huge cycles for specific values. In this example the breakpoint will point stop when the index reaches 40.

Using Node.js with Visual Studio Code you can press the debug tab and add a configuration similar to this:

You can run the debugger by pressing F5 or pressing the green play button.

Call stack

The red part of our first example represents the call stack, which is the path that your program has taken to reach the point were you set a breaking point or were you have an error.

Taking into account the example we saw earlier:

(function testing(){

var obj = {

add

} function add(a, b) {

var result = a + b

return result.split('')

} var stringResult = obj.add("1", "2") // stringResult becomes "12"

var numberResult = obj.add(1, 2) // numberResult is never set, an error is thrown

})()

Let’s see this example in order:

- testing is automatically called since it’s an IIFE (immediately Invoked Function Expression);

- obj variable is declared with the function add (using ES6 shorthand for functions in objects, it would be the same having

var obj = { add: add }; - the function add is called from the obj variable with two strings has parameters, there are added which makes them “12” in this scenario and then split is called before returning [“1”, “2”];

- the function add is called again, this time with number, the values are added making it 3 but then, split (which is not available for number type variables) is called which makes an error being thrown;

This decomposition is easy enough when you are more than used to seeing code but for someone starting out it could probably be a challenge (not wanting to underestimate people that are starting but I believe is preferable a more obvious example than a more convoluted one).

Paired with breakpoints it is easier to create a code execution in scenarios like this by taking into account the call stack which is available, for example, in chrome developer tools “sources” tab.

I’ve added a debugger statement and when running the code above you can see the “history” before reaching that breakpoint. In this case it’s not a long call stack but you can start to see why it is useful, you know the function add was executed in line 14, with what parameters (which you an see in the scope below the call stack) and you can evaluate whatever will well you at that point in the console, in this case evaluation result.split(‘’) would show you that the result being returned would be [“1”, “2”].

If you press continue the call stack will show the changes, this time add being called in line 15 instead of 14 with numbers instead of strings, try and evaluate result.split(‘’) at this point and an error should be thrown.

Hopefully at this point it will make you realise sooner that you should maybe change the name of the function to something like “concatenateAndSplit” and validate the type of the arguments.

The call stack it’s better to navigate when you have names to your functions, meaning that if you use anonymous functions you will most probably have an harder time since the call stack will not show the name of the parent function.

For example, if we remove it from the object and call it directly not much changes, but if we remove the name of, let us say testing function, the call stack will no longer be able to point you the origin of the call (you can still press the underline and it will show you but that is an extra step that could be avoided.

I would not insist in using the object to have the function, but I would recommend vividly of adding names to your functions whenever possible so that the call stack is more readable without having to dive into each step.

Another way to see the stack trace at any given point in your code is to just write console.trace() were you want to log it.

Handling errors

About the light blue part of our earliest example of an error message, that shows up like that when we do not handle errors properly, meaning that anything after that error will not be executed. To avoid this we usually try to catch the errors so we can gracefully fallback to a default state of our application in case of an error (this fallback can be a 404 page which is normally not that graceful but is better than a page to just stop working).

Let us consider the function we have been using up until now

(function testing(){

function add(a, b) {

var result = a + b

return result.split('')

} var stringResult = add("1", "2")

var numberResult = add(1, 2)

})()

By now we know that this function will break when we send a number, this could be handled by checking for the type of the arguments like we discussed before and sending something back. It would work in this one since we only have to worry about string but in other scenarios we might have to check for all other types, making our function “half validation, half logic” which can be cumbersome to read and maintain.

An alternative it’s to encapsulate our problematic function code with a try…catch which would make an error be thrown but this time, not “uncaught” so we can send it to a error logging to be checked later and send a fallback to the function so that our code continues without problems.

(function testing(){

function add(a, b) {

try {

var result = a + b

return result.split('')

} catch (error) {

console.error('add went wrong ->', error)

return [] // default value

}

} var stringResult = add("1", "2")

var numberResult = add(1, 2)

})()

This will make your error message show up slightly different and instead of a console.error you could have some kind of logging system as pointed before so you can check your client errors and fix them without waiting for a report.

The worthiest outcome of using try…catch tough is the fact that your application will keep on running, maybe with some side effects due to the fact that numberResult now contains an empty array but at least it didn’t just crash onto itself (just make sure the code you have afterwards is bearing in mind the default values of the errors).

I would recommend using try…catch when the type checks are becoming “longer than your function logic”, when a request is made and you aren’t sure if the response might change or temporarily when a code is continuously giving you problems and you still haven’t got around to refactor it.

Tools to avoid runtime errors

JS is not a compiled language like Java so your errors will happen at runtime, that means that you can only see whatever is wrong with your code after your run it.

Thankfully, to save us quite some time you can use tools like:

- quokka to evaluate your code as you type

- eslint to make sure your style guide is consistency and it will grab you an error or two along the way and

- For those of you looking to make JS a more strong typed experience you can check out stuff like TypeScript (like I said in a previous article, when learning I rather avoid libraries that abstract the core language so I wouldn’t recommend this last one when starting).

Conclusion

Being able to read error messages and practising debugging is one of your biggest weapons has a developer, do it frequently and with enough time you will notice a great decrease in the time you spend on each error that you find along the way. And remember, before a commit/push, remove all the debugging stuff from your code, we don’t want the client or another developer to get stuck on a debugger now do we?

Article 5 of 30, part of a project for publishing an article at least once a week, from idle thoughts to tutorials. Leave a comment, follow me on Diogo Spínola and then go back to your brilliant project!